Pathways to Circus Legitimacy: The Library

This article was originally published on CircusTalk in May, 2021.

Like the rest of the world, American circus artists have spent the last eighteen months largely out of work, unemployed and stunned. Although we often joke about how careers in the arts are fragile, the pandemic has made many circus performers in the US understand in very real terms how little institutional support there is for our field.

Whenever a recession hits the United States, the arts and entertainment industry is one of the first to buckle, as we also saw after the dot-com bubble collapsed in the early 2000s and again in the aftermath of the Great Recession later that decade. Historically, these economic recessions are accompanied by what some economists call a “social recession,” a years-long period where conditions within a country deteriorate, leading to a contraction of the country’s social, cultural, and artistic spheres. Social recessions are marked by their length. Between 1971 and 2006, the United States endured five economic recessions, four of which were short, lasting less than a year. The corresponding “social recessions” had an average duration of five years each. [1]

As the summer comes around, the CDC relaxes restrictions, and American performers scramble to get work, we need to remember to ask ourselves: What can we, as a circus community, do to ensure we endure the next recession? What can we do to ensure that we, and the art form we love, suffer less next time?

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act into law. Image source: National Endowment for the Arts

Many within our field are quick to answer that the situation would be different if the American circus industry could rely on funding from endowments, foundations, or governmental institutions, such as the National Endowment for the Arts. (After all, they support other art forms–why not us?!) This often happens in the same breath as comments about the “otherness” of circus and how it’s a natural home for expression that subverts the status quo. The professionalization of American circus does not have to mean the gentrification of American circus. Getting recognition from the Establishment does not mean “selling out” or betraying the essential spirit of our art form. It means curating the American circus archives– translating our love for the craft into a language that they understand, carving our own place within the American institutional life, and working to understand what outside forces have led to the state of today’s industry. Simply put, in order to gain access to this kind of support from “outside the circus tent,” there is a lot of work to do. We need to demonstrate to the outside world that not only are we interested in the practice of circus, we are interested in the elevation of circus as a performing art with a unique history, culture, and role within American society.

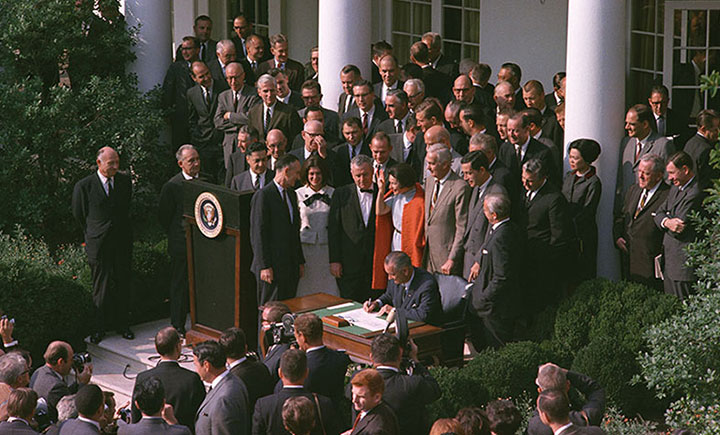

There are no accredited higher education circus schools in the USA, though a handful of schools have started the process. (Accreditation being the processes of “legitimizing” an institution of higher learning within the State of its jurisdiction, allowing it to offer a recognizable diploma rather than a certificate which holds no clout in the outside world.) [2] One of the final steps of accreditation under the American system is to have a functioning “Learning Resource System”. [3] (Broadly speaking, this is a library stocked with resources that are integrated into the school’s curriculum.) Although many circus schools in the US have a bookshelf or two, these collections fall far short of what’s needed by accrediting bodies: not only are these collections unmanaged and often not integrated into the school’s curriculum, in many cases there isn’t even an inventory of the books that make up the collection. Given that circus schools in the US generally have limited resources, this shouldn’t be surprising. Book-learning gets relegated to the back-burner in these institutions because a library (no matter how well-managed!) won’t bring students to a recreational silks class. The school needs to be financially viable before it can consider the years-long process of building a library and getting accreditation.

In my experience, this culture of “back tucks before books” has noble (if pragmatic) intentions – the labor market these students will enter is based in spectacle, not in academic lectures from educated acrobats. Yet, this attitude does a disservice to our field. [4] By emphasizing technique in this way, we’re telling young artists (explicitly or not) that spectacular circus skills are themselves the end goal, rather than tools to be used for creative expression. The artist simply “shows off what they can do” instead of exploring the relationship between the performer and the skillset. [5] This trend of skills-based instruction is a classic “chicken or the egg” paradox — do we teach this way because there isn’t a robust infrastructure to support an academic curriculum? Or do we lack funding because of this skills-first approach?

To put it plainly: Can you imagine someone graduating with a degree in a “legitimate” fine art like painting or sculpture without understanding the history of their field, its notable participants, and how past efforts helped shape the present? Why should circus professionals be held to a different standard? Why is our “fine art pedagogy” lacking the substance of other art forms? [6]

Paradise Will Be a Kind of Library

The Conjuring Arts Research Center in Manhattan, which houses over 12,000 volumes. Image source: Conjuring Arts

To start, a lot of books about the circus aren’t particularly helpful. Many titles about the circus gush about how wonderful certain performers or companies were, neglecting detailed descriptions of the performances they actually put in the ring. [7] Compare this to any other fine art, such as sculpture or painting, and the stacks of books that line their libraries’ walls and fill the syllabi of their introductory courses. Even closer to home, in the worlds of magic and clowning, such libraries exist. Both sleight of hand and physical comedy are fields of study with storied pasts, just like the circus arts, and their shelves are brimming with titles full of nuance and detail. The circus “library” isn’t in the best shape –and this phenomenon has consequences. By singularly emphasizing acrobatic technique over the stories of performers who have come before us and the realities of the markets they worked in, we’re graduating circus practitioners who don’t understand the history of their skills or the context of their own careers today. By ignoring an entire field of study within the circus — the field of understanding circus — schools essentially tell their students that this history is unimportant — that circus is about what the individual does, rather than an interconnected web of practitioners advancing an art form through their individual and collective actions.

I hasten to add that, on a practical level, many of our industry’s leaders also see the individual artist as unimportant. To quote a 2017 interview with Cirque du Soleil CEO Daniel Lamarre on the subject of buying The Works (a production company that specializes in magic shows): “Like us, they have no stars… the show is the star, and they’re constantly using different [performers]. The fact that they’re not focused on stars gives you scalability” — a sentiment he reiterated in 2019 when speaking about Mindfreak closing on the Las Vegas strip. All of this is to say, if the largest employer of circus artists in the world sees today’s individual performers as irrelevant to the company’s success, and today’s performers consider yesterday’s artists as irrelevant to their own careers, what does that mean for the future of our craft?

By neglecting our history, we’re dismissing our predecessors and their work. Their work is what has allowed us to perform our own work. Professionals in the US today often learn from their coaches and their own “on the fly” experiences, ignoring the 200 plus years of development in the circus arts. They ignore (by choice or otherwise) the performers who came before them, their decisions made and struggles overcome while building their own careers. This is sometimes framed as a pursuit of “authentic” experiences (or, to read more cynically: experiences unfettered by outside information). [8] To be glib, it’s rude to stand on the shoulders of a giant and not acknowledge that giant’s efforts, whenever they took place.

To illustrate the point more concretely, how many times has a passer-by suggested to a handbalancer “That’s impressive –now do it on one finger!”, to be met with a (well-deserved) eye-roll and a quick “Yeah, that’d be cool, but that’s impossible!” Our handbalancer has never seen the stunt done, and has no reason to believe that it would be possible in the first place. Wouldn’t it be more interesting to respond, “There are a handful of people still doing that trick today!”– then read about the methods Unus, [9] Paulinetti, Hall, and others used to perform that skill night after night?

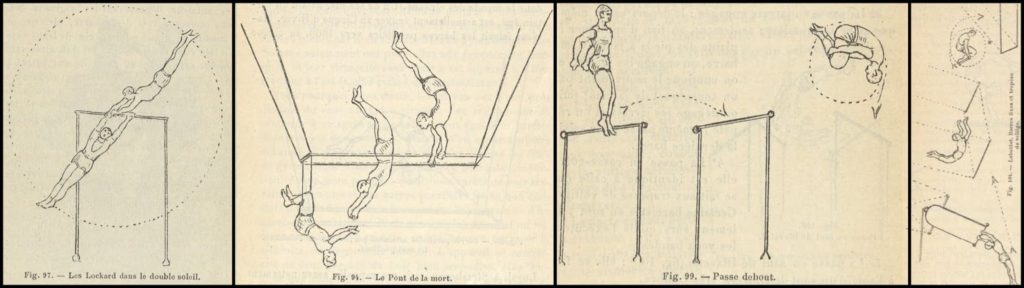

Or, perhaps, would the “innovative” high bar acts from Cirque du Soleil’s Corteo or Totem have been described a different way, [10] had the reviewers leafed through Strehly’s L’Acrobatie (1917) [11] and seen the off-the-beaten-path highbar designs detailed there? We often struggle to find “the next best thing,” not realizing that the groundwork was laid (and forgotten about) often as long as 100 years ago. [12]

Illustrations from from Strehly’s L’Acrobatie (1917). From the author’s collection

Be that as it may, we run into the same issue as before. Even if today’s student knows what they’re interested in, what good is it if they don’t know where to find it?

Though circus schools are clearly important stakeholders when it comes to attitudes and perceptions of the circus, the responsibility doesn’t stop with them when it comes to preserving and passing down our shared history. Cultural gatekeepers — performing arts centers, universities, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) — also tend to overlook the circus, and not just on their library shelves. In fact, they don’t officially see Circus Arts as its own artistic discipline at all. This is most salient when speaking with the directors of circus schools — who are forced to describe their goings-on as either “theater” or “dance” when applying for licenses, writing grants, or speaking to regional arts groups.

Circus scene. Crowds in front of Hagenbeck and Wallace Circus sideshow tent. Image source: Library of Congress

Circus (which is no more “theater” or “dance” than dance or theater are themselves interchangeable terms) is seen as something different than the arts you see on drop-down menus when applying for grants. Arts is shorthand forfine arts — that is, a creative medium to be appreciated for its aesthetic, imaginative, or intellectual content above all else. When America’s cultural institutions established their scope, the circus was as big as Hollywood — a for-profit industry (that is, one with the sole purpose of money-getting rather than contributing to the emotional life of the audience) [13] which brought in millions by offering popular entertainments. It wasn’t a fragile artistic tradition that needed outside support. It was a uniquely commercial, American enterprise (read:not art). It seems that the first step to being seen as truly legitimate on an institutional level is having your own subheading. Circus is not simply an acrobatic “flavor” of theater, nor is it “dance: other” or “performing arts: miscl.” It’s circus.

Happily, there has been movement on this front.

Leaning Towards Recognition

In 2020, the Modern Language Association (MLA) began a concerted effort to broaden their bibliography’s coverage of Circus Arts, as members of their leadership realized circus disciplines were under-represented and under-indexed within it. The MLA is the largest and oldest curated academic bibliography — and it seems the number of circademics producing work about the circus has been noticed by the cultural gatekeepers. This is one of the first steps for circus professionals to eventually win grants earmarked for their own specific disciplines (not “dance” or “theater”) as well as the other trappings of an art form held in high cultural regard in our country. As other institutions see circus professionals approaching their field in ways they recognize as being serious, rigorous, and more-than-just-spectacle, I believe they will ultimately follow suit, offering opportunities earmarked specifically for practitioners of our own corner of the performing arts.

Moreover, in the time between drafting and publishing this missive, a group of circus professionals announced the launch of a new circus arts advocacy initiative: The American Circus Alliance(ACA). In the launch meeting, which took place on April 22nd, 2021, interim board member Mark Lonergan summed the organization in brief: Collective action. That’s the major theme of this organization. Most excitingly (and, perhaps, most dryly), the ACA has partnered with Be An Arts Hero, a 501(c)4 organization that opens the door to direct political action and lobbying on behalf of the circus arts [14] — a kind of activism hitherto inaccessible to American circus artists.

There is movement. American circus is finding institutional traction. We’re waking up from a collective hibernation.

And it’s not just movement on a top-down, institutional level. Quality information is becoming more accessible to inquiring circus minds, as well. Just in the past year, a number of remarkable new titles have hit the shelves — helping “close the gap” by making well-written, interesting, original research and writing about the circus more accessible. [15] This helps artists in our own community better connect with their disciplines and industry while also signaling to the outside world that yes, this is something worth talking about. This is something worth dedicating time to. This is what we do with our lives.

In order for the Circus Arts to be seen as “legitimate” in the eyes of cultural gatekeepers, we need to treat it like a legitimate art form by cultivating — together — a greater understanding of our shared history and challenges faced by those who blazed the paths we find ourselves walking down now. [16] The value of this practice transcends simply “knowing a lot of facts” — rather, by taking an interest about circus — in elevating circus– we take the field from “trade” to “profession.”

In a field where so much importance is placed on developing a unique style, a signature trick, and building a career for oneself, it’s easy to lose sight of our commonalities. Circus is a tradition of support and community, and we were all drawn to it for one reason or another. We’re here for the love of the circus and because we want the art form to continue. By tapping into our shared history, we grow stronger as a community.

The American circus (and its allied arts!) has survived every economic crisis in this country since John Bill Ricketts built his Philadelphia amphitheater in 1792. The question isn’t ‘Will the circus survive?’ The question is ‘What condition do we want to leave it in for future generations? ‘

What’s next for American Circus? Well, that’s up to the American circus community.

Footnotes

[1] For more on this, read The Arts in a Time of Recession by Miringoff & Opdycke

[2] Note that this is in no way a rejection of the certificates given by American circus schools today. Certificates play a role in signaling to others within our industry about our network and training. When a student graduates from NECCA or Circadium and adds that to their CVs, employers “inside the circus tent” have an idea of their skill level. Outside accreditation–and the resulting diplomas–offer the rest of the world an idea of the level of training in the real world context outside of the circus community.

[3] From the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC) Standards of Accreditation: Substantive Standards, section 7: “A learning resource system includes all materials that support a student’s educational experience and enhance a school’s program… [it] must include materials commensurate with the level of education provided… [and] be integrated into a school’s curriculum and program requirements as a mechanism to enhance the educational process… managed by qualified personnel… [with] written policies and procedures for [the resource system’s] ongoing development.”

[4] To paraphrase R.G. Collingwood, the 20th century British aesthetic philosopher: Crafts arise from step-by-step processes and do not necessitate reflection, introspection, or spontaneous choice to produce (baking cakes or building tables, for example.) These are utilitarian endeavours, often with a decorative quality of some kind. Arts, however, are a form of “imaginative expression” that arise from- and are shaped by- mental activity and preserved in some medium.

[5] In the theater, this would fall under the purview of dramaturgy. Dramaturgs “…contextualize the world of a play; establish connections among the text, actors, and audience; offer opportunities for playwrights; generate projects and programs; and create conversations about plays in their communities.” (Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas.)

Dramaturgs in the circus are few and far between, though their work offers important context for today’s performers. In his 2017 piece, “Dispelling the Myths of Circus,” Belgian circus dramaturg Bauke Lievens asserts “…that [today’s circus performance] is mainly about circus itself, and only rarely about the world,” and that this “over-identification with the romantic image of the circus” (read: a surface-level understanding of “the ghost of circus past”) “has made us start to believe in the myth of authenticity.” These are notes from a European denizen of the circus world — if these criticisms apply to Europe, where professional circus schools and organizations enjoy varied levels of governmental support… what could that mean for the state of circus at home?

[6] Or, to be blunt, are we a “fine art” because we say we are? Or, what other lenses can we look at our field with and to find faults that are holding us back?

[7] The best description we have of the legendary Enrico Rastelli’s act, for example, is a page of notes written by juggler Bobby May some 46 years after he saw Rastelli in the ring. In the papers, this extraordinary display of skill was often just described as non plus ultra and left at that.

[8] It was some twenty years into this writer’s own performance career that he read that both Bobby May and Gil Dova referred to the pro-juggling lifestyle as “living in the isolation ward.” It’s comforting to know that touring as a solo act has always been difficult, and there’s a kind of comfort and camaraderie to be found in that shared experience — even though our careers were shaped by different times entirely.

[9] Of these three performers, the “one-finger stand” is most associated with the legendary Unus, who performed through the early 60s.

[10] To be clear, different doesn’t necessarily mean better. In my opinion, audience members would be better served understanding that these disciplines are the result of centuries of development — not (at worst) a “gimmick” or (at best) a “ ‘new’ technique” that serves a single show. This book, which was the first to describe modern acrobatic technique, describes (and illustrates) a number of high-bar routines with qualities that fit the description of these shows’ “innovations”.

[11] My company, Modern Vaudeville Press, is currently working on an annotated English translation of this seminal text. The full version (in the original French) can be found on Gallica here.

[12] We can see evidence of this phenomenon happening with Cirque du Soleil’s Volta and the hair hanging act there. Once this “long-lost” discipline was “reintroduced” to the world by dint of its inclusion in a major show, it grew in popularity within the circus world. However, this discipline had never actually gone anywhere– the discipline has been a staple at traditional circus schools (such as La Universidad Mesoamericana in Puebla, Mexico, et al.) for ages. Is the issue that there are so few coaches who understand nuances in training the discipline? That’s just another reason why it needs to be written down in detail – so our shared history isn’t lost.

[13] For more on this, one need look no further than PT Barnum’s monograph, The Art of Money Getting. In the same essay, Barnum relays sound advice that might have come in handy before this industry-shattering pandemic: “Every man should make his son or daughter learn some useful trade or profession, so that in these days of changing fortunes of being rich to-day and poor tomorrow they may have something tangible to fall back upon. This provision might save many persons from misery, who by some unexpected turn of fortune have lost all their means.” Barnum and his legacy still inhabit the minds of the American public — and here, he indicates that the people of his day see “circus skills” as (at worst) not a useful trade or profession or (at best) applicable only to a fragile market… and his immediate market was far-and-away larger than that of modern times.

[14] For readers unfamiliar, the not-for-profit organizations they interact with on a day-to-day basis are likely 501(c)3 groups — apolitical organizations with a community-driven focus (the American Youth Circus Organization and the International Jugglers’ Association are examples of these.) 501(c)4 organizations tend to have a much narrower (and usually political) focus, and are allowed to engage in unlimited lobbying activities (MoveOn.org and the American Civil Liberties Union, for example.) Thanks to stipulations in the American tax code regarding charitable donations and tax deductions, things get really interesting when a 501(c)3 and a 501(c)4 partner up. If you’re interested in more on this, check out this article by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy.

[15] This is due in part to the advent of print-on-demand publishing, which allows small and independent presses to distribute niche titles without the need for significant overhead. Stewards of the Circus Arts have more tools at their disposal than ever before! This technology has eroded the power of traditional gatekeepers, such as major publishers who want to sell books by the million– not esoteric titles on circus spectatorship, lost disciplines, and long-dead acrobats.

[16] If you want to see what we’re up against culturally, I challenge you to read this press release from TGI Fridays without rolling your eyes. Does Circus mean “Fine Art” or “Amazing Blazing Pound of Cheese Fries”? In either event, the developers of this multi-million dollar marketing stunt explicitly refer to the Circus motif as an avenue for nostalgia. To them, Circus is something that was. And that message is going out to every strip mall in America. Today.

Special thanks to:

Kimzyn Campbell

Benjamin Domask-Ruh

Fritz Grobe

Madeline Hoak

Sophie Lewis